José Brunner, historian and philosopher of science, is the grandson of the Jewish Buchenwald inmate Maximilian Brunner and a member of the Scientific Board of Trustees of the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation. He lives in Israel, in a suburb of Tel Aviv, and has lectured as a professor at Tel Aviv University. His work focuses, inter alia, on coming to terms with history and conceptualizing traumas. José Brunner was, inter alia, a visiting professor at the Friedrich-Schiller University in Jena and at the Sigmund Freud Private University in Berlin, and editor of the journal History and Memory. José Brunner was scheduled to deliver his speech at the commemorative event at the German National Theatre in Weimar on 5 April 2020.

A Plea For Diversity

I am writing this text in a suburb of Tel Aviv; it should have been given as a speech at the German National Theatre in Weimar on the occasion of the commemorative act for the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 5 April 2020. In Germany, all commemorative events to mark this occasion had to be cancelled due to the spread of the Coronavirus. Here in Israel, too, I am under lockdown on account of the Corona pandemic and can no longer leave the house. An invisible danger lurks outside. It is uncanny to commemorate the liberation of Buchenwald under such circumstances. Parallels do come to mind, which I immediately dismiss. They strike me as contrived: shielding oneself from a virus is not akin to trying to hide oneself from the Nazis. A virus does not hate; it does not persecute anyone, and should it kill, it never has any murderous intentions. But as with the Holocaust, it changes the world. What yesterday seemed a matter of course and a certainty is today no longer so. Overnight we have lost our existential security. Despite multiple differences, this experience now strangely re-connects me with my grandfather. His life was also unexpectedly torn apart at the seams.

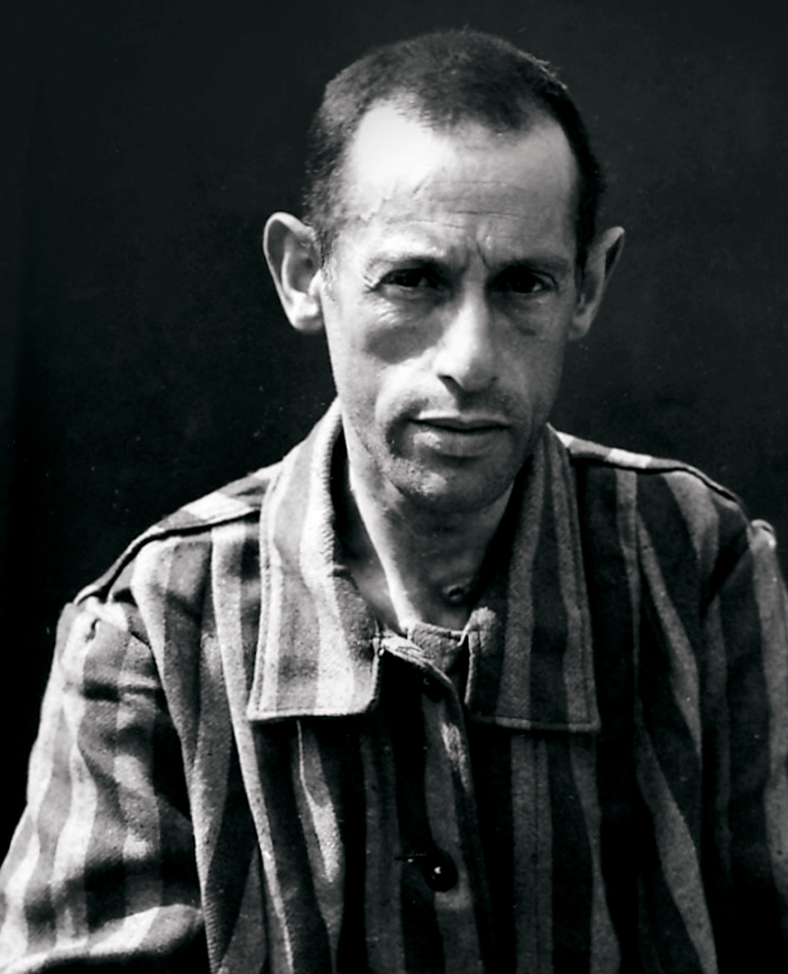

From First Lieutenant to Inmate

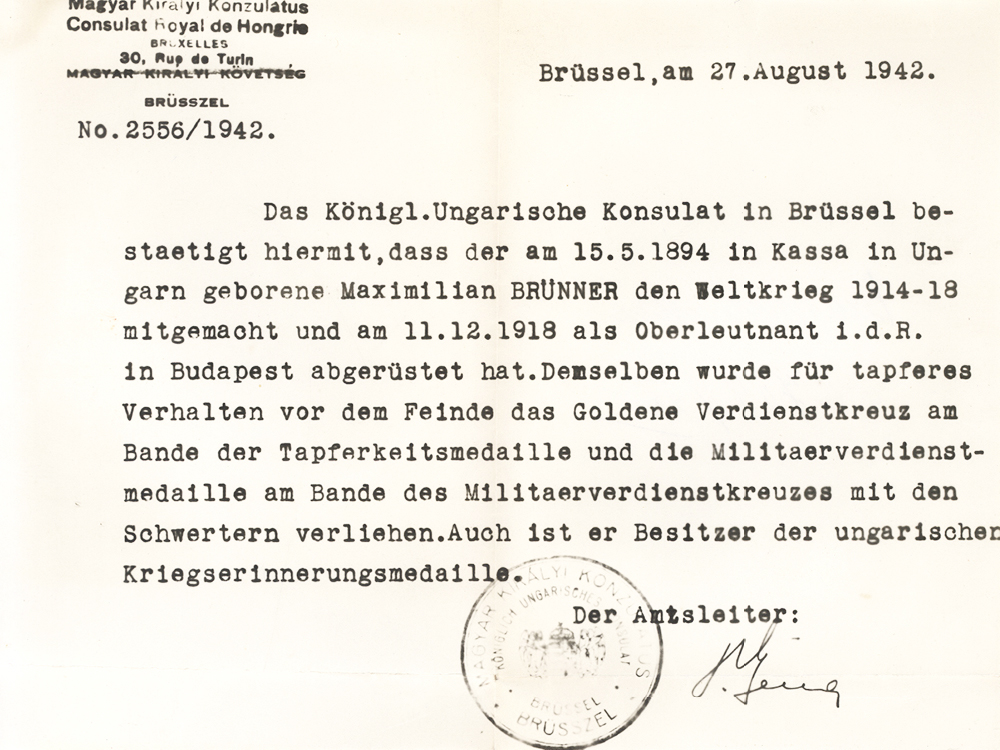

Maximilian (Menasche) Brunner, Grandpa Max to me, was born in 1894 in Kaschau (also known as Kassa or Košice), a large city in eastern Slovakia that then belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and where Jews had already settled in the 16th century. Although he came with his family to Antwerp at the age of four, he nonetheless returned to serve as a volunteer in the Imperial and Royal Army of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (k.u.k.) during the First World War and was awarded the Golden Cross of Merit and several other accolades in the war’s aftermath. Following demobilization as a First Lieutenant, he made his way back to Antwerp in December 1918, where he was to become a diamond cutter.

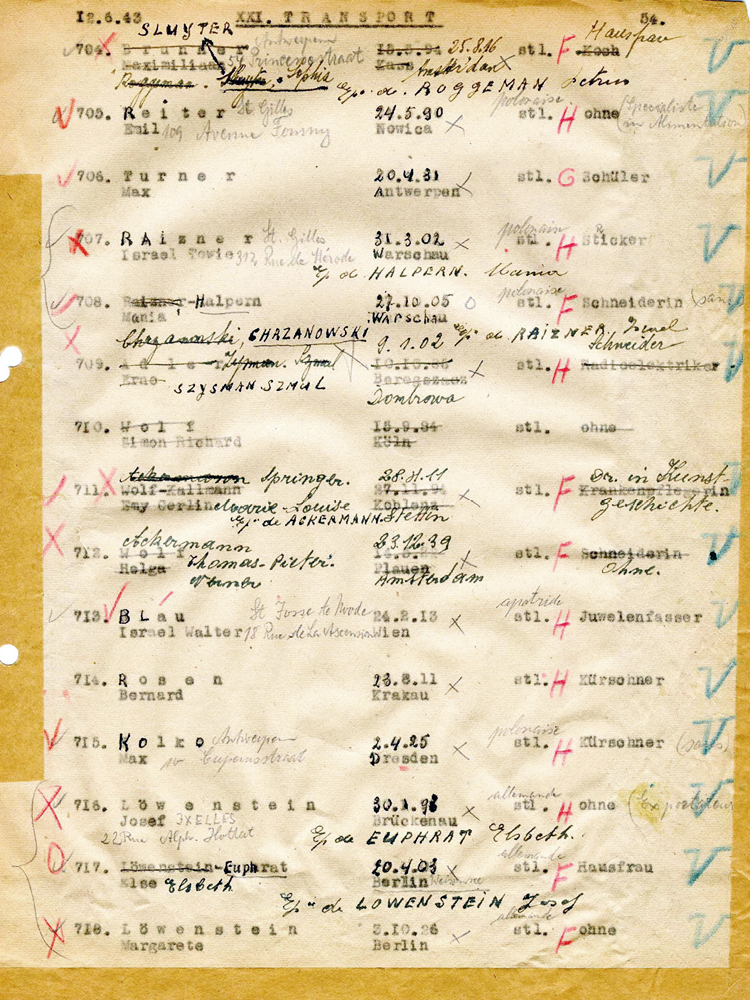

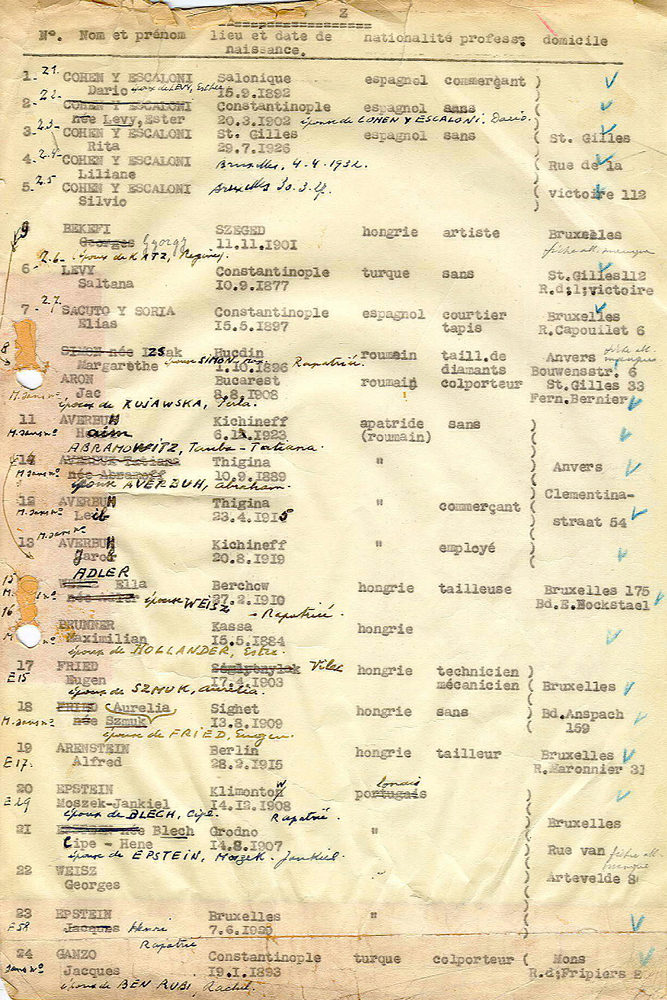

In May 1940, the Wehrmacht invaded Belgium after which persecution of Jews was to begin in July 1942. My grandfather obtained forged papers both for himself and his family along with a hideaway with the Balzat family in Genval, an idyllic small town in Wallonia. He nonetheless dared to go to Brussels every now and then. Gestapo agents caught up with him there, dragged him into a basement and beat him to pulp in order that he reveal the whereabouts of his family’s hideaway. He refused to provide them any information. Disfigured beyond recognition, he was sent to the SS Mechelen transit camp, located between Brussels and Antwerp. From there, more than 25,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz to be murdered. His name featured on the transport list to Auschwitz for 12 June 1943, as prisoner number 704.

As a former Austro-Hungarian Army officer, however, Max succeeded in obtaining a letter of protection (Schutzbrief) from the Hungarian Consul in Brussels.

Given that the German killing machinery had to proceed in an orderly fashion, his name was duly struck off the list and replaced by 25-year-old Sophia Sluyter. Six months later, once Himmler ordered the deportation of the remaining Jews imprisoned in Belgium, my grandfather was sent with the Z transport to Buchenwald on 15 December 1943, this time as prisoner number 16, to Block 22, the Jewish block. This completed his transformation from a First Lieutenant in the Austro-Hungarian Army and an Antwerp-based diamond cutter into a Buchenwald inmate.

Hierarchies and Solidarity

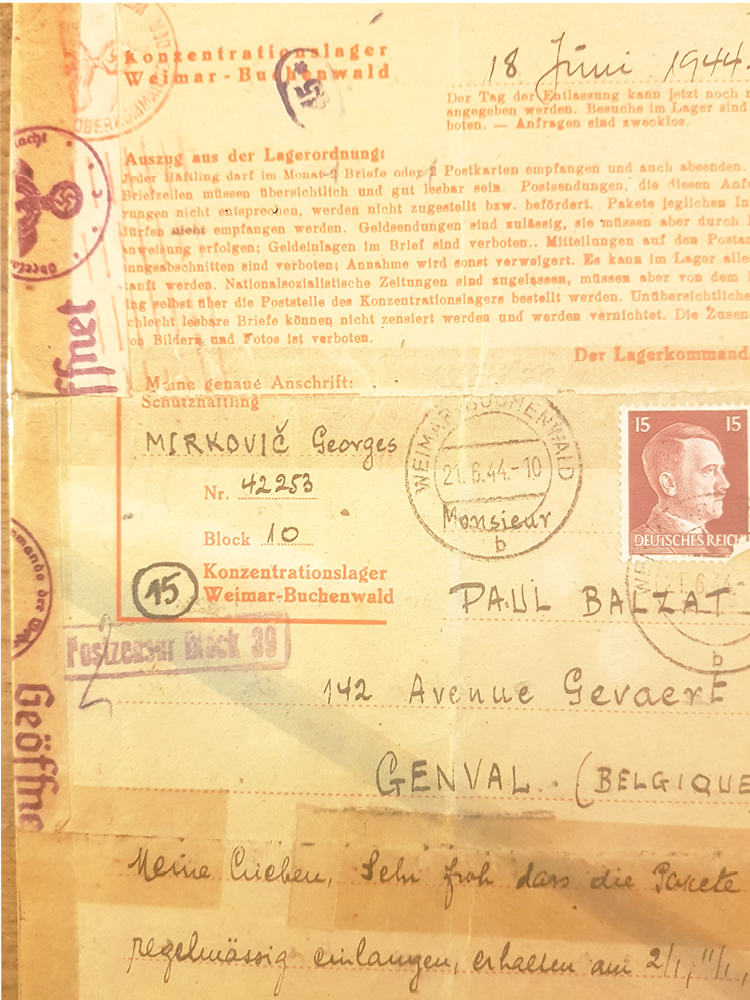

Every month political prisoners in Buchenwald were permitted to send one letter to their families to ask for aid packages. Jews were denied this privilege. My grandfather, as ingenious as ever, came to an arrangement with two Serbian political prisoners, whose villages had been destroyed and families murdered. They had no living relatives to whom they could turn for help. Max still had a family, but was not permitted to write to them. So, the two Serbs gave him the sheet of writing paper to which they were entitled and he sent it on behalf of Georges Mirkovič to the Balzat family in Genval, where his wife Esther, my grandmother, his daughter Dora, my aunt, and his son Henri, my father, had found shelter. Max asked for money, clothes, and food provisions. In this regard, too, the German bureaucracy proceeded smoothly; the packages duly arrived. Max and the two Serbian inmates shared everything and thus managed to survive.

My grandfather also used this money to help Belgian political prisoners. For this, and for other forms of resistance against the camp guards in Buchenwald, the Belgian state honoured him with the Croix de Chevalier de l’Ordre de Leopold II Avec Palme and the Croix de Guerre after the war––and, regrettably only in the wake of his demise.

I am telling Grandpa Max’s life-story in such detail not only because I want to honour him on this occasion as one of the many people who expressed solidarity in the concentration camp, but also, and above all, to plead that no one ought to be remembered merely as a victim. People came to Buchenwald from many different countries and under differing circumstances. Reducing them to their victimhood, without acknowledging the diversity of their identities and destinies before, during, and after Buchenwald, would ultimately entail adopting the perpetrators’ perspective; they did not consider those inside the camp as unique individuals, but merely as inmates who, in their eyes, were all sub-human.

To emphasize the diversity of those imprisoned in Buchenwald, yet who were not merely prisoners, constitutes a challenge we have to confront with even greater rigour the further removed in time we are from those bygone events. This is possible only if we do not restrict our remembrance to generalizing formulas and set rituals, if we do not commemorate an abstract collective of victims, but rather speak of individuals whose names, origins, mother tongues, and biographies we cherish and whose memories we safeguard.

Together, these men and women from different nations, the political prisoners, the Jews and Jehovah's Witnesses, the Sinti and Roma, the children and the elderly, the homosexuals and those otherwise socially discriminated who were imprisoned in Buchenwald, constituted a microcosm that represented the whole of Europe. And each had their individual life story, before, during, and – if they survived – after Buchenwald. It is critical to underline that even within the confines of the concentration camp these individuals did not fuse into a single amorphous mass. There were gradations and hierarchies amongst the prisoners; everybody was not equal in the camp; opportunities were available for breaking down barriers and showing community spirit.

Tradition and History

On arrival, my grandfather was put to work inside Buchenwald as a bricklayer, before being subsequently dispatched to a workshop for cutting and polishing optical lenses outside the camp. According to our family lore, that workshop belonged to Zeiss. I am aware that no historical evidence exists of a link between Zeiss and Buchenwald. I also know that historians treat contemporary witnesses as foes. However, while they often talk as though all the facts about the Holocaust have already been dug up and researched, it was not that long ago that Germany suddenly started remembering the millions of forced laborers whose deportation had been orchestrated by the General Plenipotentiary Fritz Sauckel right in the heart of Weimar. This recollection only took shape amidst the German public after class action lawsuits against German companies were filed in the United States.

I would thus like to warn against letting only documents speak or believing that every stone has been overturned when it comes to research. Who knows where the truth about the workshop in which my grandfather was forced to work is to be found? In the archives that historians have researched, or in my family’s private oral transmissions? Obviously, I cannot pass any judgement on this matter. I can just state that there cannot be only one – homogeneous and official -––history of Nazi crimes and the Holocaust. Just as a tightly-knit rope comprises multiple individual fibres, this history must also remain dynamic and multi-stranded. If this history is not to fossilize into dogma, scope must remain for divergent traditions and testimonials.

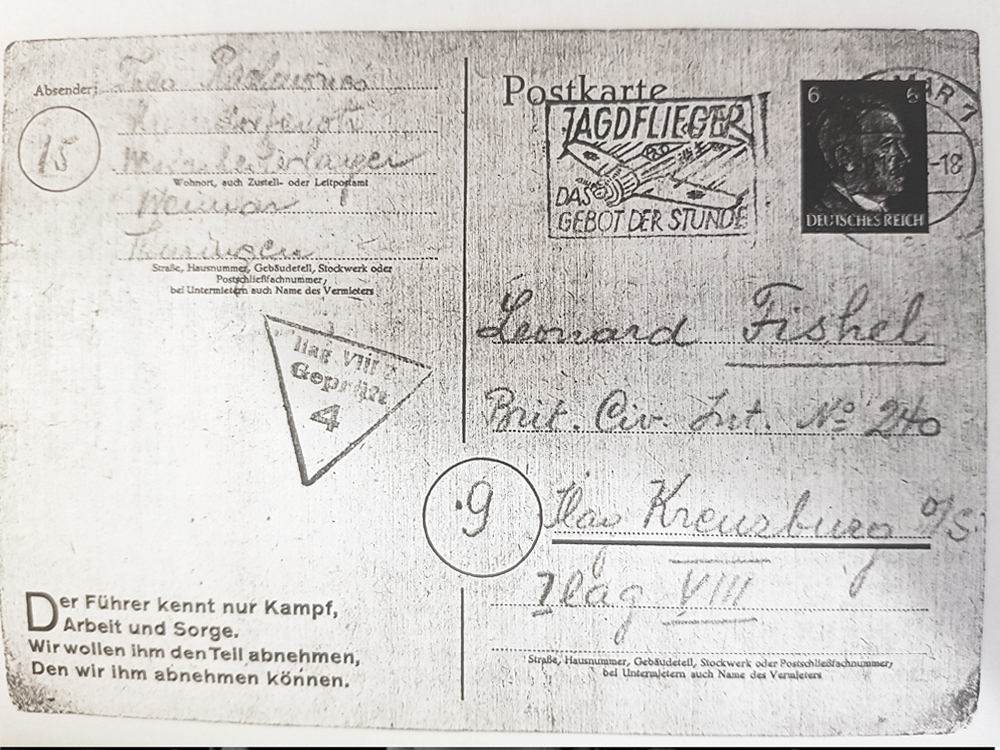

A Postcard

Apparently, my grandfather succeeded in developing contacts with people in the workshop, who were not imprisoned in Buchenwald. My family received a postcard in his handwriting, but posted from outside the camp, from Weimar, to his daughter’s boyfriend, addressed to his future son-in-law Leonard Fishel, who at the time was interned in Silesia because he had been an English Jewish resident in Antwerp. My grandfather signed the postcard as “Theo Rachmunes” : Theo, the Greek for God, and Rachmunes, the Yiddish for mercy. “God have mercy,” or “God the Merciful.”

This postcard thus reveals how in Buchenwald my grandfather still retained his taste for humour and did not relinquish his sense of irony. Moreover, it attests to the fact that he never allowed himself to be debased.

This postcard has yet another meaning. When the Auschwitz survivor and Israeli author Yehiel De-Nur, who called himself Ka-Tzetnik, was called as a witness to the Eichmann trial, he described Auschwitz as “another planet.” In his words, some of which surely sound familiar: “The time there is not the same as it is here, on Earth. ... And the inhabitants of this planet had no names. They had no parents and no children. They didn’t dress the way we dress here ... they breathed according to different laws of nature; they did not live ––and die–– according to the laws of the world here.”

What Dinur had to say about Auschwitz equally applies to Buchenwald. Although Buchenwald was not an extermination camp in the literal sense of the term, the customary laws that governed people no longer applied in that concentration camp. And yet, both Auschwitz and Buchenwald were located on this Earth. As with the majority of Germans, following the liberation of Buchenwald the good citizens of Weimar acted as though the concentration camp was on another planet of which they knew nothing. But the simple fact that my grandfather worked in a workshop outside the camp and that he somehow managed to have a postcard sent from Weimar illustrates that they didn’t only observe Buchenwald from afar. They evidently also came into contact with the camp guards and the inmates.

It was not primarily the camp’s electric fence that separated Buchenwald’s inmates from the people of Weimar, however. More significant were the inner barriers that the city’s residents had erected in their minds and hearts. These barriers enabled them to perceive the camp as part of their everyday lives, and yet at the same time to ignore or even approve of the meaning of what was going behind that electric fence, and while retaining an immaculately moral self-image of themselves. Naturally, the possibility to deliberately separate knowledge concerning injustice, cruelty, and murder from its moral significance, or even to frame it in a morally positive fashion, not only existed back then and not just with regard to Buchenwald. To this very day, such behaviour continues to horrify.

And just as Buchenwald was an inherent part of Weimar at that time, Weimar cannot now disassociate itself from Buchenwald. For Buchenwald was not built on a distant planet, but rather on a nearby hill called Ettersberg, where, in his day, Goethe would go for a walk. Even after the camp was constructed, some people were still able to stroll about this landscape. Karl-Otto Koch, Commander-in-Chief at the camp, ensured that a park area for the SS guards was constructed just outside the camp fence. It featured a birdhouse, a water basin, and a mini zoo that housed four bears and five monkeys. The animals thrived there, within eyeshot of the camp’s inmates.

Here again, it was not just barbed wire that separated the camp-guards’ families, as they sauntered through the park and visited the small zoo, from the inmates. Rather, it was an inner barrier that enabled them to entertain such callous cynicism. It was this rank cynicism that distinguished the SS-guards from my grandfather; his quiet irony demonstrated that he, unlike them, had retained his humanity.

What does it mean to survive?

Max Brunner survived. Fearing that the camp guards would murder the Jews in the camp as the Americans began their approach in early April 1945, he hid himself with the help of Belgian comrades in the Invalid Block, where he once again was able to assume a false identity. This time it was that of a French inmate who had just died. The camp was liberated on 11 April and on 28 April my grandfather along with other survivors from Weimar were flown to Milan by the Americans, and from there back to Brussels, where he fell into the arms of my grandmother and my father on 3 May .

Max not only displayed courage, ingenuity, solidarity, and a sense of irony ––above all, he was lucky, incredibly lucky. But, he also knew how to facilitate good fortune. He managed to adapt to constantly changing conditions and circumstances, and invariably sought out fresh solutions and ways to defy adversity even under the direst circumstances. This ability helped him to survive, for the Holocaust did not erupt into history in the way a wooden board shatters a pane of glass. Rather, it developed gradually; initially by exclusion, followed by persecution, and culminating in annihilation. The Holocaust was no accident; it was not an event outside of history. The Holocaust was part and parcel of history; its origins, its continuation as well as its aftermath were embedded in history.

Though my grandfather came back alive from Buchenwald, he died in 1962 at the age of sixty-eight, probably owing to the damage his health suffered in the concentration camp. Hence, one final history lesson. Liberation does not mean the end of persecution. Even though the Buchenwald survivors scattered to every corner of the Earth, re-joining their families, their villages and cities, or launching new livelihoods in foreign lands, they henceforth had something in common. Buchenwald remained embedded in their souls and bodies; an invisible yet enduring presence that does not define the person, but nevertheless affects him or her permanently.

The perpetrators, too, men and women alike, returned home, and mostly remained unpunished. On their part, too, something endured and endures to this day: a political conviction that conjoins hate, racism in its every manifestation, and authoritarianism. Howsoever it mutates, this conviction constitutes a force that continues to threaten minorities and the socially disadvantaged. It does not tolerate diversity. It threatens all those considered foreign and inferior by the Nazi perpetrators’ political progeny and their followers. In contrast with a virus, no vaccine is available against this violent and destructive political faith, which time and again threatens to become an epidemic. That's why we have to resist it over and again. Reminding ourselves of Buchenwald will help us do so.

Prof. Dr. José Brunner, Tel Aviv

Sources:

Brunner, Henri: “War Memories 1940-45”, 2000, as yet unpublished.

Brunner, Max: “Testimony 1404” Yad Vashem Archives, 1959.

Fishel, Melvyn George: “Caught in the Torments of the Shoah”, 2019. www.fishel.net/shoah.html.

Szeintuch, Yechiel: “Ka-Tzetnik”, in: Dan Diner (Ed.), Enzyklopädie jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur, Stuttgart, Springer-Verlag, 2011–2017.