Wolfgang Huber, former Bishop of Berlin and former President of the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany, was responsible for the publication of the new edition of works by Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Protestant theologian and resistance fighter murdered by the Nazis, who was also imprisoned in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Wolfgang Huber, who also happens to be Bonhoeffer’s biographer, was due to give his speech as part of the commemorative act on 7 April 2020 at the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp Memorial Site.

Now more than ever – resistance against the “hell called Dora”

Marking the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp

Anton, Berta, Cäsar – “Dora”: The German phonetic alphabet gave the concentration camp in Nordhausen its name. The spirit of schematizing and classifying was thereby imprinted on this site, for it was merely a matter of the letter “D”. “Mittelbau” was soon to be coupled with it. This quickly linked the site to around 40 other sub-camps in the Harz Mountains, in which people of differing origins were robbed of their freedom. As forced labourers, they were actively furthering German armaments projects and other such schemes.

To end up in the Dora camp meant having to spend day and night for months on end in underground tunnels. These tunnels were supposed to be expanded into subterranean production facilities for those “miracle weapons” through which the “ultimate victory” could still be won. Work was carried out without any safety measures in place; workers had to confront life-threatening falling boulders on a daily basis; stone dust infiltrated their lungs whether at work or when trying to get some rest. In the “hell called Dora”, forced labourers came back from their work famished and exhausted. Malnourished, they struggled to catch some sleep under inhumane conditions. At times they would even lie down on the body of a dead person so as not to have to stretch out on the bare ground. In many cases utter exhaustion led to a swift and cruel death.

The fate of 13 million forced labourers mirrors that of those who perished or those who had to live in fear of their lives at the Dora camp between 1943 and 1945. The physical violence to which they were subjected on a daily basis was preceded by a violent mindset that had gripped an overwhelming majority of Germans. This mindset certainly did not emerge during the Nazi era for the first time. The terrain was already ripe for such an outbreak because of the pervasive and excessively nationalistic sentiment, which had by no means diminished due to the nation’s defeat in the First World War; for many, defiance even grew on account of the lost war and a peace that was widely perceived as unjust. National Socialism appropriated this sentiment and combined it with the crudest racism, especially, and from the outset, in the shape of anti-Semitism.

Anyone who nowadays wonders about the radicality with which Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount spells out how murder begins with contempt and disparagement of other human beings need only recall the mass murders that took place in camps such as Auschwitz and Dora. Because these mass murders demonstrate how killing begins with words and thoughts; otherwise put, they begin with such attitudes. Whenever forced labourers were driven in trucks through Nordhausen, children who saw them passing by would fling stones at them. They were just following up the attitude they had absorbed from their parents with action.

Radicality involves grasping matters at the root. Grasped at the root, murder begins with contempt and disparagement of others. Genocide begins with contempt and disparagement of other peoples. Racism and anti-Semitism constitute basic forms of such degradation. Wherever they spread, again, that which happened millions of times in camps such as Auschwitz and Dora will once again become a possibility. Our memories are no longer fed on the certitude that something comparable could never be repeated. This reminder is necessary, for something comparable is still possible. We owe it to the victims not to let their memories fade into oblivion. The state and civil society have to face down with clarity those bringing the perpetrators’ demons back to life.

For some time now we thought we had jettisoned misanthropic hatred and collective contempt; we thought we would have acknowledged the inviolability of human dignity taking responsibility for the guilt of our darkest years. Against such a backdrop, a democracy ought to have taken root in Germany that is contingent upon the recognition of identical human rights for each and every one. We were proud that this spirit was shaping the Germany that has been united since 1990. Yet, we now realise that this is anything but a certainty. We need to be shaken up by these acts of violence triggered by hatred and contempt toward foreigners, as well as toward those who protect them out of a sense of political responsibility. The extent to which anti-Semitism is once again on the rampage – and not only through words but also in the actions that follow upon those words – must not leave us complacent. We can no longer consider a liberal, human rights-oriented democracy as an unquestionable given.

In his speech to the German Bundestag in remembrance of the victims of National Socialism, Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier drew the veil of trivialization aside. In his 29 January 2020 address, he stated: “I wish I could […] say: We Germans have understood. But how could I say that when hatred and rabble-rousing are spreading yet again, when the poison of nationalism is seeping into public discourse – in our very midst as well? [..] We thought that the pernicious ideology would fade away over time. But no: the sinister demons of the past have now assumed a new guise. What’s more: they flaunt their ethnic, authoritarian thinking as a vision; even as the better answer to the open questions of our time.”

We not only encounter the horror that is currently spreading whenever such a demon is reflected in deeds in the memories of the Dora concentration camp. We also discover the spirit of resistance amidst these memories, upon which we are dependent once again. Hence, we thank the survivors for their resistance, for without such a spirit of resistance they would have lacked the strength to survive. We equally remember those who perished in the concentration camps or whose lives were marked after their release by the previous ill-treatment; lives that often remained scarred until succumbing to an untimely death.

The range of lifestyles and attitudes to be witnessed in the survivors’ testimonies is correspondingly wide. I think of Lili Jacob, who, utterly exhausted after her liberation, was taken to a former SS shelter that had been converted into an infirmary. In the nightstand beside her bed she happened to come across a photo album that an unknown SS man from Auschwitz had brought to Mittelbau-Dora. On leafing through it, she discovered photos of her grandparents, her parents and even of herself. All her relatives had been murdered; but at long last she had final signs of life from them. These were to become all she had in the world, from which she took courage to start afresh.

I think of Hanns Chaim Mayer, who also started life anew after his release from the camp under the nom de plume Jean Améry. It wasn’t until 1964 that he dared to process his experiences in Auschwitz and Mittelbau through literature. For him, the worst experience was torture, to which he devoted an essay under the title “Die Tortur” [Torture]. Whoever survived torture, he insisted, bore its marks for life, both physically and mentally. As Améry extrapolated from his own experience, torture undermines one’s trust in the world in a way that cannot be compensated for. His very existence remained a life on the edge. He expressly derived the right to end his own life from his biography. Not only did he publicly announce this in a book; he also exercised this right and died by his own hand.

Harassed as a Jew, Heinz Galinski had been forced to do hard labour in Berlin since 1940; that did not spare him, however, from being deported to Auschwitz, where his wife and mother were murdered. He was carted off to the Mittelbau concentration camp in January 1945. He was liberated in Bergen-Belsen after being forced on yet another death march. Galinski transformed these traumatic experiences into a scarcely credible force. Together with his second wife Ruth, he devoted his later years to rebuilding Jewish life in Berlin. From 1949 to 1992, he chaired the local Jewish Community in Berlin; in his final years he linked this to the chairmanship of the Central Council of Jews in Germany. When I came to Berlin in 1994, soon after Galinski’s death, I could immediately hear and feel to what extent and with what forthrightness he had shaped the Jewish presence in West Berlin; he had made it an indispensable element in a new civil society. Considering the harrowing experiences from which his commitment was born, it is only all the more admirable.

Time for Outrage! The call to arms rang out belatedly. It is also linked to the Dora concentration camp. Stéphane Hessel is the last case in point I wish to mention. Born a German, Hessel became a naturalised French citizen who served in Charles de Gaulle’s government-in-exile in London during the Second World War. It dispatched him to Paris, where he was captured by the Gestapo, who then deported him, a Resistance member, to Buchenwald. He narrowly escaped the hangman through a highly risky identity swap; his identity was changed for that of a prisoner who had succumbed to typhus. His unsuccessful escape with a comrade was equally daring; as a result, he ended up in the Dora camp, which was considered even worse than Buchenwald. Having survived the war, he decided to devote his life to human rights. To this end, he joined the French diplomatic corps, which sent him as a delegate to the United Nations where he was an observer to the editing of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was to become his political creed.

This is the background for the plea that Hessel addressed to the general public in 2010: Time for Outrage! The word “outrage”, which gave the slim volume its title, was derived from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It states in the preamble that “disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind.” Hence, Stéphane Hessel’s plea was not about indignation by angry citizens, but rather about the outrage of the human conscience when confronted with barbaric acts arising from the non-recognition of human rights, derived from an attitude of hatred and contempt.

This outrage by the human conscience with respect to human dignity is a basic attitude that has currently become so brittle in many parts of the world; indeed, some are even asking whether the time for human rights is over. Against such resignation, it remains to be said that this outrage is a virtue that must regain strength. May the number of people increase who come together at an early stage to successfully resist any violation of elementary human rights wherever possible. Together with many other places, the “hell called Dora” obliges us to heed this plea.

Wolfgang Huber, Berlin

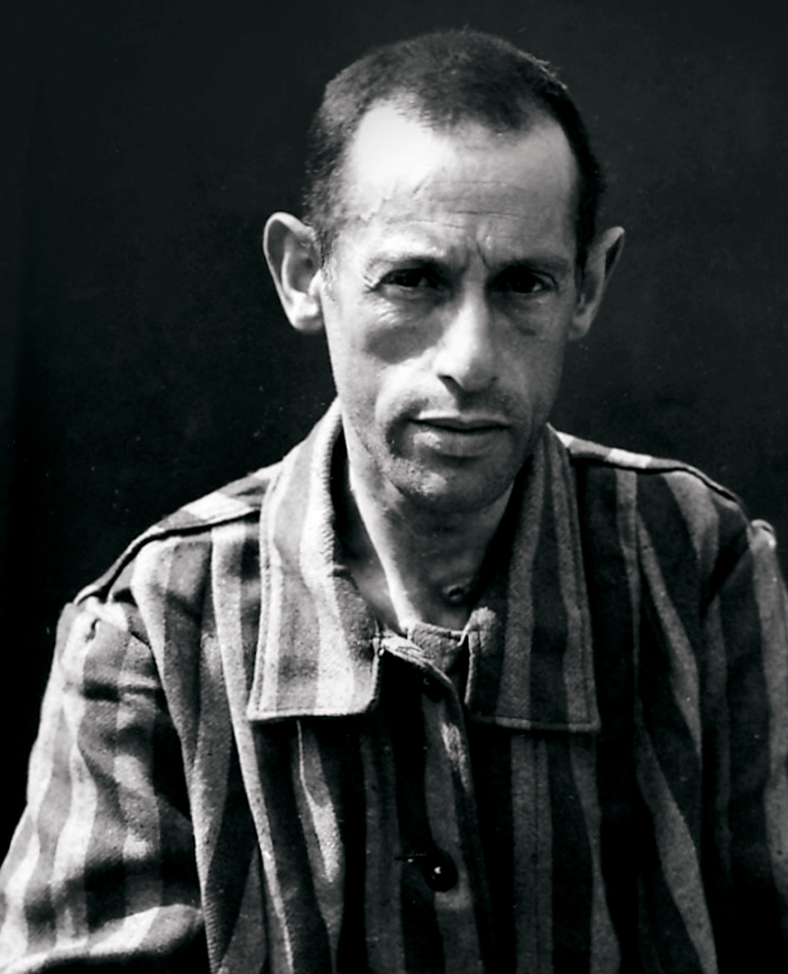

Wolfgang Huber during a lecture on Dietrich Bonhoeffer as part of an event by the Buchenwald Memorial Site with the German National Theatre Weimar to mark the 74th anniversary of the liberation of Buchenwald on 9 April 2019