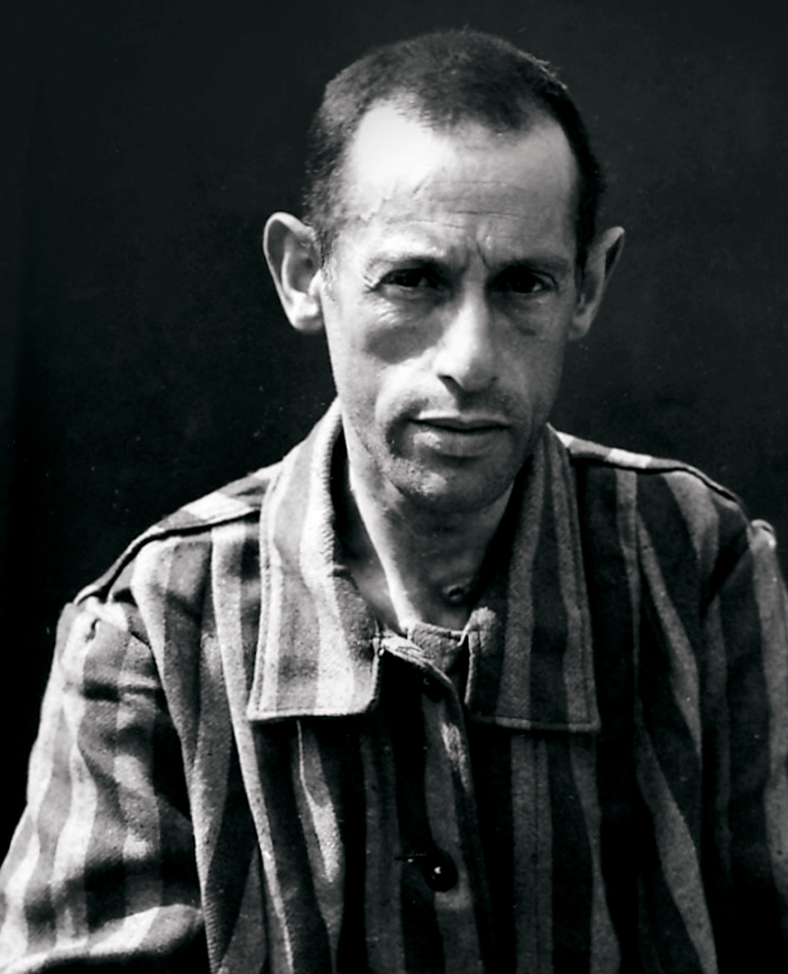

Ivan Ivanji, born in Banat in Yugoslavia in 1929, who, as a Jew, was deported to Auschwitz and Buchenwald in March 1944 after the Nazis had murdered his parents in Belgrade. He was liberated at the Langenstein-Zwieberge satellite-camp. He now lives in Belgrade as an author and publicist. In 2014, his life-story was published under the title Mein schönes Leben in der Hölle [My Beautiful Life in Hell]. Ivan Ivanji was due to deliver his speech as part of the commemorative act at the German National Theatre on 5 April 2020.

Speech to be delivered on the occasion of the 75th Anniversary of the liberation of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

The Außenkommando (sub-camp) of the Buchenwald Langenstein-Zwieberge concentration camp was split into a large and a small camp. Some 6,000 inmates were interned in the large camp; they had to dig tunnels under the nearby hill, in which Vergeltungswaffen [V-weapons] were to be produced . The 869 prisoners barracked in the small camp were considered as hard-to-replace skilled-workers and hence afforded better food rations and treated a little better. On 9 April 1945, the SS assembled a column of 2,500 prisoners who were driven westward from the camp on what was to become a death march. Those who remained behind in the camp no longer had to go to work. No more food rations were served, however.

People died of hunger and exhaustion, particularly in the large camp.

On April 11, the searchlights were no longer switched on in the evening and suddenly the rumour spread that the SS had left. The camp’s portal lay ajar. Nothing had yet happened. The great Death continued. I needed to go to the latrine in the middle of the night. Something blocked my way in the dark. I kicked the obstacle aside with my clog and then noticed I had kicked the head of a corpse. And I thought to myself that one day I would “wonder” how I had stepped on the head of a deceased fellow inmate. Yes, I am still thinking about that moment. Yet, am I just wondering? Should I characterise this horror, this disgust as a matter of “wonder”?

That’s enough of that. I don’t want to take part in a big contest of who can better lament, or describe their suffering in more harrowing terms. I would rather talk about the liberation, victory, freedom and the traps they set for us.

On 19 April 1945, the surviving inmates in the Buchenwald main camp made a pledge. Although I was not present, I feel obliged to keep this pledge. A key sentence in the pledge runs:

“The destroy Nazism, root and branch, is our motto. Our objective is to build a new world of peace and freedom.”

Have we kept this pledge? I don't think we have. Recently, the German Federal President Steinmeier stated in Jerusalem, I quote:

“I wish I could say that we Germans have once and for all learned from history. Yet, I can't say that, as hatred and rabble-rousing are spreading.” With this statement, President Steinmeier substantiated the fact that neither the destruction of Nazism nor the establishment of a world of peace and freedom have been successful. Let me add, peace and freedom across the entire world.

When the German President delivered that speech two-and-a-half months ago, I still believed that the neo-Nazis could never again take power here in Germany. I can no longer think that as inconceivable. As though I didn't have enough horror in my native land of Serbia, I watched with concern and terror developments here in the country where the Buchenwald concentration camp is located. Given how right-wing lawmakers are ridiculing and undermining democracy, it’s not just about Thuringia, it’s not just about Germany. I'm afraid it's about the very idea and the existence of parliamentary democracy. Everything is in a state of flux. Everything.

Fifteen years ago, in his speech at the National Theatre in Weimar on the occasion of the Liberation Day, Jorge Semprun declared, among other things, that that celebration was probably the last such encounter with the camp’s survivors, and he added - I quote - “In ten years, there will be no more direct reminders, no first-hand testimonies, no living memories; the experience of that Death will have come to an end.” He got it wrong, for five years subsequent to that occasion, he made another big, moving speech on the Ettersberg hill, at the camp’s former parade ground. Moreover, this year some of the surviving Buchenwald prisoners were due to come to Weimar, had not this natural calamity–– this virus that has proven just how powerless we modern humans are when confronted with nature––hampered us from making the journey.

For some of us former inmates, this encounter on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the liberation would have been our farewell to the memorial-site. In the foreseeable future, that can be said of all survivors. It's of little import what we so-called contemporary witnesses think and want, all that really matters is what our grandchildren and great-grandchildren remember and what lessons they want to learn.

In the context of remembering the Holocaust, it has been repeatedly emphasized how critical it is to protect minorities. This primarily has meant the Jews. Gradually, however, we have come to understand that communities such as the Sinti and Roma, who have no backing such as the State of Israel, were also impacted and in many places are still affected, discriminated against and outlawed. In fact, anti-Semitism is spreading once again. In my opinion, however, this should not be equated with the oft-justified criticism of the government in Jerusalem. As a Jew, I would like to stress that we are not the only minority in need of respect and protection. In Israel, the Palestinians are in need of such. And here in Germany, as in other countries, it is now the refugees. I urgently implore you all to empathise with those who are persecuted today; those who have had to flee, who are maltreated at the borders, who are perishing and starving in camps, and drowning in the seas. Do not say that these are other circumstances, different situations, that these people might have other reasons to flee from dangers, or might be entertaining illogical and unrealistic dreams of paradises in Germany, Sweden, or wherever. Don't seek out any justifications or excuses to look aside, to shrug your shoulders and ignore the suffering of these people. I ask all of you this, for I, too, have lived through and experienced the Shoah.

Someone who has shaped the design of this memorial-site like no other for more than a quarter of a century is also about to bid farewell to Buchenwald. Volkhard Knigge will take his leave of Buchenwald. The community, which will continue to fly the flag there, will say goodbye to him. Energetic, active, imaginative people have occasionally to give offense to others, to endure injustices, and sometimes make mistakes. And Volkhard Knigge is energetic, tirelessly active, and full of ideas. He has also made enemies. In my view, that stands to his stead. The memorial site will remain in good hands. Not only will the new director guarantee that, but also the fact that the tireless, irreplaceable Philipp Neumann-Thein will remain active. I think I can speak on behalf of all former prisoners when I wish them every success, and naturally that applies to all current and new employees.

And then, yes, I had longed to go to Weimar once again, to speak there again, and bid my farewell. I had wanted to do that five years ago, but I couldn't. On the very day I was supposed to be there, on 11 April 2015, my wife Dragana died. I had already prepared my speech for the act of commemoration at the National Theatre at that time. Volkhard Knigge delivered it in my place.

Buchenwald, Weimar –– at 91, I no longer dare say auf Wiedersehen, or until we meet again. From a distance, I bid you farewell – Adieu.

That Death be Forgotten!

Long Live Life!

Ivan Ivanji, Belgrade

Ivan Ivanji during his speech at the memorial service of the Thuringian State Parliament for victims of National Socialism at the Buchenwald Memorial Site, 27 January 2013